Rothwell Grammar School was built after a long hard fight by local politicians. It was very nearly strangled at birth by government officials but finally opened in 1933. Its genesis goes back as far as 1902 when an education act transferred responsibility for primary, or elementary, education from school boards, which had existed since the 1870s, to the county and county borough councils. The act enabled working class children who won scholarships at the age of 11 to be subsidised to attend old established grammar schools and before the First World War there was a trickle of pupils catching the train or tram to go to schools in Wakefield or Leeds. Meanwhile the majority stayed on at the elementary school until they were 13 which was raised to 14 in 1918.

The act also allowed councils to set up their own grammar schools and after the war, as the Labour Party began to gain a firmer foothold on the West Riding County Council, plans emerged for a new school. It was to serve a population of about 40,000 in the working class townships of Rothwell, Lofthouse with Carlton, Oulton with Woodlesford, Ardsley East, Stanley, Outwood and Kirkhamgate.

In 1925 a suitable site became available when the owner of Lofthouse Hall, Benjamin Saville, decided to sell off a large area of land, parts of which had once been a Roman camp and a Saxon homestead. Saville had made his money as a “dry salter” dealing in dyes for the clothing trade in Hunslet. The previous occupants, from the 1850s, were the Ramskill family. Parsons Ramskill had also been in the chemical business and his unmarried son, Josiah, who qualified at Guy’s Hospital in London as a surgeon, lived at the hall with a cook and two servants. Ramsgate opposite the school is named after him and there’s a Saville Close off Carlton Lane.

The first problem the planners had to overcome was mining subsidence. The District Valuer was against use of the site for a school but he was overruled and 17 acres were acquired in 1927 although it was agreed to wait at least three years for the ground to settle before building work started. One option would have been for the council to pay for a “pillar” of unmined coal to support the building but that was deemed too expensive. In the end it took several years longer because of opposition from civil servants at the Board of Education in London. They had to give their approval for the council to borrow money for construction and they were not convinced of the need for a new grammar school at all.

The West Riding argument led by the chairman of the education committee, Sir Percy Jackson, and councillor William Henry Turner, who was a market gardener in Robin Hood, was that a Rothwell school would make it much easier, and affordable, for local children to take up secondary education.

Sitting in Whitehall the officials had little understanding of the lives of local mining families. In good times the men took home as little as £3 a week and often much less as they were laid off or on short time. Even for a child who won a County Minor Scholarship it was hard for their parents to pay for the extras of travel, meals and clothes for them to go to the Wakefield or Leeds schools. Without a scholarship it was practically impossible to pay the tuition fees of up to £25 a year.

The civil servants were also suspicious of the Rothwell Urban District councillors’ desire for a school as part of efforts to thwart a “land grab” by Leeds City Council to swallow up their area. They had already resisted two attempts and hoped the school would help consolidate their local power and reputation.

Eventually in June 1929 the civil servants caved in. Officially it was the growth in the numbers of eligible children caused by the post-war “baby boom” of 1920 and the shortage of places in Wakefield that convinced them, but it’s no coincidence that a month earlier Labour had won power under Prime Minister Ramsey Macdonald. He appointed Sir Charles Trevelyan to be President of the Board of Education. Trevelyan had been the Liberal M.P. for Elland so he must have had some local knowledge. In an unusual move for a “toff” he had swopped sides in parliament and there’s no doubt he was much more easily persuaded of the need for a new grammar school than his Tory predecessor at the Board.

Designed by county architect Henry Wormald the new school had accommodation for 360 pupils which could easily be raised to 465. There were 10 classrooms on the ground floor and science laboratories on the first floor, plus a gym and an assembly hall which doubled as a dining room. The architect wanted separate woodwork and metalwork rooms but they had to be combined after yet more interference by penny pinching bureaucrats in London. The total cost was about £40,000, which equates to about £1,400,000 today.

The first day of the first term was Tuesday 12th September 1933 when 81 pupils arrived to be met by just six teachers: the headmaster Mr. Manley along with Mr. Jeffery, Miss Clegg, Miss Robinson, Mrs. Liversedge and Miss Hartley, who took a special interest in the “cleanliness and hygene” of the girls. By the end of the first year the numbers had risen to 95 with over half of them on scholarships, the rest paying an annual fee of £9 9 shillings or 9 guineas as it was known.

Bulk buying was used to keep the cost of uniforms down and Mrs. Kirby, the caretaker’s wife, cooked the school dinners which cost 2 shillings a week. The groundsman, George Wilfred Merry, doubled up as a rugby coach. Savings were encouraged with the opening of a branch of the Yorkshire Penny Bank, a school museum was started, and guest lecturers were invited. One of them was a Wakefield Trinity player who talked about a tour to Australia.

A parent teacher association was formed headed by Councillor Turner. He led them in a variety of fund raising activities including a garden party which paid for stage curtains, a cricket net and camping equipment. For the first school magazine he wrote an article on his favourite subject, rhubarb.

From the start social and sporting activity was just as important as classroom learning and each child was a member of one of four houses. An official had suggested naming them after the four Rothwell freeholders in the Domesday Book but Harold, Bared, Alric and Stainulf didn’t sound right so they were named after people who had achieved “fame after a life-time of effort.” Hence explorer David Livingstone, scientist Michael Faraday, nurse Florence Nightingale, and missionary Wilfred Grenfell.

Sadly one of the boys, Philip Law, died from diphtheria during the Christmas break something that was not uncommon in those days and there were strict quarantine rules if an infectious disease affected a child’s home.

A feature of school life which was established early on was the annual “exchange” with students from France. One of the first trips was during the Whitsuntide holiday in 1939, just a few months before the outbreak of war, when a group of pupils set off by train for Le Mans along with Mr. Manley. The boys stayed at a French boarding school whilst the girls lodged in local homes. The group took some lessons at the school and the rest of time was spent exploring the Loire valley.

The school had its first inspection during February 1940 when the pipes were frozen and water had to be delivered by tanker. Farcically the caretaker fell over some buckets just as the inspectors were being introduced, “disturbing the solemnity of the moment.” By then there were 17 teachers and 290 pupils, mostly on scholarships. They mainly left at 16 after taking their School Certificate exams, the majority going in to clerical jobs in factories, offices, and on the railways. At that stage there were only 17 in the sixth form and the first pupil to win a degree was Douglas Hartley who went to Birmingham University.

Possibly stating the obvious the chief inspector wrote: “The mental equipment of the pupils does not appear to be high. They do not come as a rule from homes where books are numerous and as far as intellectual training is concerned the school has everything to do for them. The pupils have not, as far as can be judged, that robust physique which will enable them to stand any great strain.”

Another comment which was not shown to the governors was more ominous. It reflected the disdain of the bureaucrats who nearly prevented the establishment of the school and is recorded in government files at the National Archives in London. It reads: “It is very doubtful whether there was ever any necessity for a secondary school in the Rothwell area. Local patriotism played a strong part in the setting up of this school. It would almost certainly be futile and in any event cause great unpleasantness to raise the question of its continued existence, but if in the future it were suggested that the building should be put to other uses the suggestion should be carefully examined.” Luckily the 1944 Education Act and the post war baby boom put paid to that.

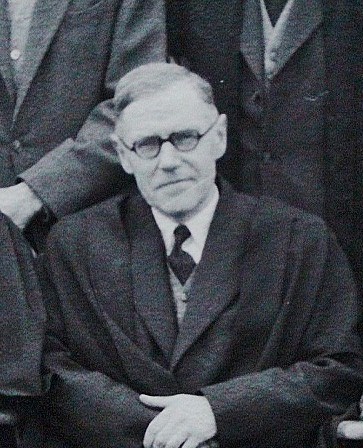

From the outset, and for next 30 years, the school was dominated by the first headmaster, Edwin Robert Manley. His educational philosophy was ahead of its time and he was clearly against the prevailing custom of cramming facts into children so that they could pass examinations. “My idea of an educated person is a man or woman with a fearless and unprejudiced mind, who has developed his natural powers to the point at which he can delight in good things, so that he can himself have a full life, and by the fullness of his own life benefit all with whom he comes into contact,” he said at the first speech day.

Politically Manley was a socialist and member of the Labour Party serving from 1946 as a Rothwell councillor for Lofthouse. He was elected chairman of the library and housing committees and served for a year as chairman of the full council. Another role was as press secretary to the West Yorkshire Association of the National Union of Teachers. On the face of it Ted, or Gaff as he was known by many of the first pupils, was an unlikely candidate to be chosen as the headmaster of a working class Yorkshire secondary school and it may well have been his politics that helped him convince the appointment board. A southerner from a middle class farming family which had its roots in Devon his father had lost an arm in a shooting accident when he was a boy and he could be difficult to live with.

Ted was born in 1899 on a farm next to the River Thames in Oxfordshire and after the family moved again he grew up at Potcote near Towcester and was taught by a governess. His older half-brother, Robert Manley, became the country’s first commercial beekeeper and honey producer. Ted’s mother was his father’s second wife after his first died in childbirth. She was from Dublin and a member of the Plymouth Brethren, an evangelical Christian sect. It was probably her influence which gave Ted an interest in drama which he brought to Rothwell with great effect as a way to improve spoken English and build the confidence of the pupils. It started with three one-act plays for the first Christmas Concert: “One of the things which impressed me most about that first batch of children was how nervous they were and how easily they cried. I was determined to put that right. The plays certainly helped make them feel at home,” he said. One girl remembered being given a prize for speaking donated by Mr. Manley’s mother.

The First World War had a lifelong influence on him, not least because he thought he had “no business to be still alive.” He remembered that when he was a boarder in the sixth form at Taunton School boys who had been sitting next to him would join the forces and within weeks they would be dead. One of his older brothers was badly injured and the brother he was closest to, Jack, who he had climbed trees and gone horse riding with, was a pilot in the Royal Flying Corps when was killed in France in 1917. His best friend drowned when the mail boat he was on was torpedoed by a German submarine.

Ted Manley was short sighted and had to wear glasses and that probably saved his life. His eyesight stopped him becoming a pilot and military dithering meant he didn’t join up until November 1917. First he was sent on a course for officers at Jesus College, Cambridge, where his commanding officer wrote: “He is hard working and has sound knowledge. He has improved much during the course and should make an efficient officer.” Just the kind of wording that he would later use in countless school reports at Rothwell!

He was posted to join the Royal Irish Fusiliers at Dublin Castle. Then just two months before the end of the war he joined the Labour Corps where his main task seems to have been an adventure around the globe as he accompanied a unit of Chinese labourers from France back to their homeland via Canada. The idea for school camps and trips to the Continent possibly comes from that experience. A portent of his lenient attitude to punishment in school may stem from being let off lightly when he was court-martialled for returning late from leave. After his journey to China he arrived back by boat from Hong Kong on 12th February 1920, was demobbed the next day, and making up for lost time in his education he enrolled at the University of Oxford the following day. There he studied Modern History graduating with a 2nd class degree just over a year later.

In 1922, at Leicester, he married Hilda Louise Ellam who was born at Louth in Lincolnshire. At about the same time he was offered a job at the independent Macclesfield Grammar School where he first came into contact with the industrial North. Ted and Hilda were there for seven years and it was during that time that his ideas about schooling and his socialism developed.

His experiences during the war, his mother’s non-conformist Irish background, his older brother’s “kitchen communism,” and the post war slump which resulted in the loss of the family farm, all played a part. But it was also the working class slums and “the wretched physical condition of many of the people” which spurred him to move to Brockley County School in the Lewisham area in what he described as a “less salubrious” part of south London. There, as the couple looked after his dying father, he threw himself into left wing politics and into the welfare of the pupils, developing the ideas which he would later put to such good effect at R.G.S. A new headmaster arrived who didn’t agree with his methods and he was thinking of becoming a full-time politician when he noticed the job at Rothwell, although he left the application in his car and it was only through the intervention of an “officious” friend of his wife that the letter was posted.

The rest, as they say, is history. The people of the Rothwell area owe a huge debt to the pioneering efforts and dedication of Ted Manley and his early colleagues and those who came after. Although not all children who passed through the doors of Rothwell Grammar School went on to a glittering career for most it was a happy and unforgettable experience. If you’d like to read more about the school an archive of material, including the first prospectus and school magazines which were saved when the old school building was demolished, is available in the local history section of Leeds library. Also there is the manuscript of an unpublished history of Rothwell by Ted Manley. Meet the Miner, a book researched during the Second World War when he was in the Home Guard unit at the school, gives an insight into a way of life in this area which has now disappeared.

Click on the links below to read a memoir by Michael Wild of his time at Rothwell Grammar School from 1952 to 1957. Much of what he writes could apply to several generations who came after him. Below the memoir are links to the school magazines from 1954 and 1955.

Ted and Hilda Manley never had children of their own and after he retired in 1963 they went to live close to his beekeeping brother and his family at Benson in Oxfordshire, a mile or so away from where he was born. There she pursued her hobby of breeding Cairn terriers and he continued to write in small caravan in the garden, publishing a series of English textbooks. Later they moved to the village of East Hendred where he wrote his last book – a history of the village. Mr. Manley died suddenly in 1970. Earlier he had written a poem called The School Master:

I only know,

That something of me, much or less, will grow,

Into the nature of the child I teach,

To nourish or impoverish, and that each,

Is so far me and all his life will bear,

Some mark of good or ill that I have planted there.