The first perpetual curate, or incumbent priest, at Oulton St. John’s church was John Kershaw Craig. He appears to have been well liked by churchgoers and helped them fight off a cholera pandemic which engulfed the country in 1832. Later in life though he was accused of having sex with several teenage girls. It greatly damaged his reputation and led to a prolonged court battle to clear his name but all that was to come over a decade after he left Yorkshire. He was also the author of several religious books, the first of which was based on a sermon he gave from the pulpit at Oulton.

Reverend Craig came from a family with Scottish ancestry that could trace its roots to Craigfintry in Aberdeenshire in the early 1500s. He was born in London in 1801 and as a child lived in a house on Charlotte Street in the fashionable area of Fitzrovia just to the north of Oxford Street. His father, William Marshall Craig, was a well connected painter of water colour portraits and miniatures. Commissions came from Queen Caroline, who was married to King George IV, and the Duke and Duchess of York as well as other members of the aristocracy.

During his education in the classical languages, including Hebrew, at Magdelen College at the University of Oxford, John Kershaw Craig visited Berlin where he met an eminent professor of divinity. He graduated with a Bachelor of Arts degree in January 1828 and a short while later he followed his older brother Edward into the Church of England. He was ordained as a deacon and then as a priest by the Bishop of Winchester, Charles Richard Sumner, a prominent member of the Evangelical School in the church.

After serving as a curate at a parish in Sheffield for about a year Craig was chosen to be the first incumbent at Oulton by John Blayds of Oulton Hall in September 1829. St. John’s church, designed by architect Thomas Rickman, was nearing completion after being commissioned by Blayds’ father, also called John. As John Calverley, born in 1753, he was descended from long standing Rothwell and Oulton families but had been brought up in Leeds where his father owned a grocery supplying wealthy Leeds cloth merchants. John became a banker, the protege of one of the merchants called John Blayds, to whom he was distantly related. When this original John Blayds and his two sisters died without children Calverley inherited his fortune and estates in Leeds and Oulton. Subsequently in 1807 he petitioned King George III for permission to change his family name to Blayds in honour of his benefactor. He died in 1827 just as building work was getting under way on St. John’s church leaving the project to be completed by his son.

John Calverley/Blayds and his son both appear to have been very religious men. As well as paying for the construction and endowing the running costs of the new Oulton church, records show they also gave generously to charities to help the poor in Leeds. In Oulton they were the benefactors behind the establishment of a “national” school for educating the children of Oulton and Woodlesford. As prominent citizens taking part in Leeds society it would have been expected of them to be regular church goers. It may be that their charitable Christian behaviour came about as a result of their enormous windfall, akin to winning the lottery today, but to give them the benefit of the doubt they were acting in much the same way as many of their newly rich Leeds contemporaries like the Gotts and the Marshalls.

From the full name of Oulton church – St. John the Evangelist – it’s clear the Calverley/Blayds family were involved with the evangelical movement in the Church of England and this would explain why the Reverend John Kershaw Craig, an avowed evangelical, was chosen as the first “perpetual curate” for the church. The movement had developed during a religious revival in the 18th century with its followers stressing lifestyle, doctrine and personal conduct. They campaigned for moral reform in society and were supporters of missions, schools and charities for the poor. A prominent evangelical was the Yorkshire member of parliament William Wilberforce, one of the leading proponents for the abolition of the slave trade, and, although there is no firm documentary evidence linking them directly, he appears to have won the vote of John Blayds in several general elections.

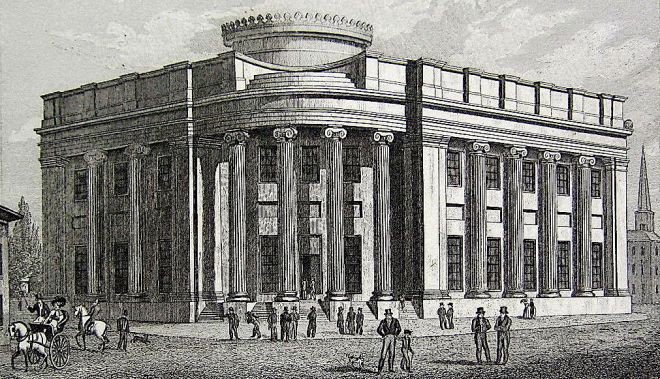

News of John Kershaw Craig’s appointment was published in the Leeds Intelligencer newspaper on Thursday 1 October 1829. It read: “John Blayds Esq., of Oulton, has been pleased to nominate as the incumbent of the new church now being built on his domain, in the parish of Rothwell, near Leeds, the Rev. John Kershaw Craig, B. A. late of Magdalen Hall, Oxford, and now curate at Sheffield. It is expected the church will be ready for consecration at Christmas next: a most beautiful and highly decorated specimen of the early English gothic architecture, and is in every respect what architects conceive a structure of this character ought to be. The cost in ornamental work must have been very considerable, for, though accommodation is only provided for six hundred persons, the whole expense of the erection will be little short of £13,000. It is built in conformity with the will of Mr. Blayds’ father, the late John Blayds, Esq. of Leeds, an act having been obtained for the purpose, and it is to be endowed, we understand, by £4,000, 3 per cents. Messrs. Rickman and Hutchinson, of Birmingham, are architects.”

Converted to today’s values the capital cost to build the church was around £800,000 with the endowment worth about £270,000. It was invested in government bonds which gave an annual income to pay for the church’s upkeep and the priest’s annual salary or “living.” Under ecclesiastical law Oulton was not then a separate parish and came under the jurisdiction of the ancient Rothwell parish hence a “perpetual curate” had to be appointed rather than a rector or vicar. Effectively the curate operated much as a modern day vicar conducting services and ceremonies but it wasn’t until the 1960s that Oulton was created as a distinct parish.

In the event J. K. Craig was suffering from some kind of illness and was too unwell to attend the church consecration on the Tuesday before Christmas 1829 and must have taken up his duties early in the new year. The first baptisms he conducted were on Sunday 11 March 1830 including those of twins Martha and Mary, daughters of William Carson, the on-site clerk of works acting for the architects during the church’s construction. The Carsons had been living at Iveridge Hall which was part of the Blayds estate. Also baptised was John Robinson, the son of gardener Thomas Robinson and his wife Sarah. A week later the first funeral and burial was that of 56 year old farmer John Farrer. Weddings didn’t start until 1832.

Very little is known about Reverend Craig’s relationship with his “boss” up at the hall or with his “flock” from Oulton and Woodlesford who had previously worshipped at Rothwell parish church. Many villagers were “dissenters” and on Sundays attended the old Wesleyan Methodist chapel on Calverley Road, although up until an act of parliament in 1837 they would have had to go to Rothwell church or St. John’s for marriage services. The registers also show that many couples, especially those with a baby on the way, went to churches in Leeds for their weddings where the reading of “banns” was less strict.

There was no local newspaper in the Rothwell area until 1873 but a few glimpses of Reverend Craig’s activities can be found in papers published in Leeds and Wakefield. For instance in August 1830 he delivered a “pleasing address” at the Commercial Buildings in Leeds at a meeting of the local branch of the Society for the Promoting Christianity Among The Jews. This is yet more evidence of his evangelical beliefs as the society, which started amongst poor Jewish immigrants in London’s East End, was supported by William Wilberforce and other leading evangelical Anglicans.

In November 1830 the Intelligencer reported that “a fine toned organ,” built by Thomas Elliot and William Hill of London, was opened in St John’s by Mr. H. Smith, organist of the parish church at Leeds. “A very impressive and appropriate sermon was preached by Rev. J. K. Craig,” said the paper.

A year later another of Craig’s sermons from the Oulton pulpit was captured for posterity in print in a pamphlet circulated around the country. It wasn’t normal for the sermons of ordinary priests to be published but this was an unusual time. In a fascinating echo of recent events a pandemic was stalking the land, quarantine was imposed on ships arriving at ports, and people were frightened that they and their neighbours might die. The disease then was cholera which had spread from Russia to the rest of mainland Europe claiming hundreds of thousands of lives. A full understanding that it was spread by a bacterium through bad sanitation and dirty water was yet to come and it was thought to be spread by “miasma” or bad air.

There were no confirmed cases of cholera in the United Kingdom as Reverend Craig preached his sermon at St. John’s on Sunday 6 November 1831 but doctors and government officials knew it was only a matter of time before the infection took hold.

Taking as his starting point a passage from the King James Bible translation of the Book of Revelation, predicting plagues and pestilence before the Second Coming of Christ, he appeared to be preparing his congregation for the worst and asking them to put their trust in God. “The time is at hand. He that is unjust be unjust still: and he which is filthy, let him be filthy still: and he that is righteous let him be righteous still: and he that is holy, let him be holy still. And behold, I come quickly; and my reward is with me, to give every man according as his work shall be. I am Alpha and Omega, the Beginning and the End, the First and the Last. Blessed are they that do his commandments, that they may have right to the tree of life, and may enter in through the gates of the city,” it read.

He went on: “I speak to you as it has now become a duty of ministers of religion, on that dreadful calamity of pestilence which is visiting and ravaging the world. Its steady progressive advancement from country to country, and now its near approach to ourselves, in having begun its work of death on the neighbouring shores, that there is cause for personal anxiety, and a solemn call to all ranks of persons, “to set their house in order, and prepare to meet their God.” For a population brought up to believe in the literal words of the bible it must have been a terrifying time.

Reverend Craig also passed on details of regulations from a government Privy Council document which had been published in the London Gazette and newspapers, pronouncements which bear a remarkable similarity to the more recent declarations of present day ministers.

“As the disease approaches the neighbouring shores, not only the necessity of increased vigilance is more apparent, but it is also consistent with common prudence that the country should be prepared to meet the contingency of so dreadful a calamity,” it said. A Board of Health was to be established in every town and village and isolated houses were to be used for the sick and dying. “All precautions be now adopted to inculcate cleanliness, sobriety, and ventilation on the people. A notice is given to draw the troops or the police around the infected places.”

Under the title “Meetness To Die: A Word From The Pulpit For The The Present Time,” the sermon was rushed into print in Leeds and London and sold for 3 old pence a copy. It should be remembered however that a majority of the parishioners at Oulton would have been unable to read or write so the sermon from the pulpit would have been their first briefing from a figure of authority. “I believe it is stated by medical men that the time it will probably reach us will be in this next Spring,” said Reverend Craig. This turned out to be a complete underestimate and the preached sermon in church was very timely indeed as a brief paragraph in the printed version noted that just the day afterwards a case of cholera was confirmed at Sunderland.

In one way the doctors mentioned by Reverend Craig were proved right as the first death in Leeds, of the two year old son of an Irish immigrant weaver, was identified at the end of May 1832. Three weeks later a short paragraph of “unofficial” news in the York Herald on 23 June claimed cholera was “said to have made its appearance at Pontefract, Brotherton, and Woodlesford.” This suggests that one way the disease may have been spreading was amongst watermen and their families who carried cargo up and down the Aire and Calder Navigation between Leeds and the coastal ports. The York Herald reference appears to have been the only mention of cholera locally and the burial registers for Oulton and Rothwell for the period do not mention cause of death so it’s difficult to estimate the extent of the disease in the area. It’s inevitable that there would have been a few cases in Rothwell parish but not to the extent that the disease ravaged the poor parts of the centre of Leeds. This is probably because villagers obtained their drinking water from deep wells which weren’t contaminated by human sewage.

When this particular pandemic was over the official death toll for the city of Leeds was 702 with graveyards struggling to cope. In the country as a whole 32,000 were reported to have died. Despite the insanitary conditions of the areas occupied by the Leeds poor being identified by a surgeon as a cause of the spread of cholera it wasn’t until after another pandemic in 1849 that proper sewers were built by the city council and completed in 1855. Incidentally one of the contractors involved in expanding the system at Knostrop in the 1860s was Silas Abbey, an Oulton quarry owner, stone merchant and builder.

A couple of months before he gave his cholera sermon John Kershaw Craig had travelled to London to marry Elizabeth Phillips at St. Matthew’s church in Brixton. She was 8 years younger than him, the daughter of Thomas Amphlett Phillips, a Royal Navy captain, and granddaughter of Henry Tudor, a highly regarded Sheffield silversmith. It may well have been a marriage arranged by their parents through a family connection.

Their first son, Herbert Tudor Craig, was born at the Oulton parsonage in July 1832 during the cholera outbreak so it must have been a worrying time for them. They went on to have three more boys – Basil, Allen and Bernard. All four of them went to the University of Oxford and in what may have been something a record, all were ordained into the Church of England. The second son, Basil Tudor Craig, born at Oulton in December 1833, emigrated to live in South Australia where he was the incumbent at Mount Gambier between 1878 and 1893.

Following “Meetness To Die,” which had only 20 pages, Reverend Craig wrote two more books whilst he was at Oulton. “Four Tests of True Religion – A scriptural standard for evil times,” appeared in June 1832 and cost 1 shilling and 6 pence. A more substantial work came in two volumes and had a bit of a mouthful for a title: “Conversion: In a series of cases recorded in the New Testament, defective, doubtful, and real: intended as a help to self-examination.” It appears to have been a collection of his sermons and was probably aimed at fellow clergyman and well off evangelicals who could afford the cover price of 10 shillings, over £30 at today’s values. A preface dated 22 November 1832 at Oulton parsonage dedicated the book to the Bishop of Winchester.

One of the religious enterprises Reverend Craig was associated with was the Newfoundland and British North American Society for Educating the Poor, a missionary organisation dedicated to setting up schools for immigrants across Canada. In September 1832 he invited Reverend William Marshall, the secretary of the society to preach at Oulton. It was no doubt an interesting meeting as Marshall was the incumbent at St. John the Evangelist at Archway in north London which had opened a year before Oulton, so they would have been able to make comparisons between their respective church architecture and congregations.

Apart from his books there appear to be no diaries or letters left behind by Reverend Craig so few other details of his time and impact at Oulton remain. Nor did the Blayds/Calverley family leave any kind of record which referred to him or any other of the priests at St. John’s. Much later an individual who knew him well wrote an unsigned obituary which described him as “a man of striking individuality of character, and powerful mind, who stood out from his fellow men with whom his lot was cast.”

He was an accomplished chess player and keen on cricket so he may well have been involved with those activities at Oulton. “He was of very courteous and gentlemanly bearing, but at the same time possessed a most resolute character and unbending disposition, and his was not the nature to be dictated to by the squire of the village or anyone else, for he always stood by his principles, and acted according to his own standard of right,” said the anonymous source.

In church he was said to conduct a simple form of worship “free from ornate and elaborate ritual.” This tradition was carried on by the next two incumbents at St. John’s but changed in the 1890s as the Calverley family and their curates became more attracted to “high church” rituals like the use of incense and white robes.

Four and a half years after he arrived John Kershaw Craig left Oulton with his wife and two young children to become a curate in All Saints parish in Edmonton, Middlesex. Today it is one of the sprawling suburbs of north London but then it was still separated from the capital by several miles of countryside. Given that both John Kershaw and Elizabeth had roots in the capital the move may have been made so they could be nearer to their respective families, or it may have about come as a request from the church authorities.

Whatever the reason it was a long journey south by one of the horse drawn coaches that left Leeds everyday and travelled via the Great North Road taking well over 24 hours to complete the journey. One of them passed through Oulton on its way along the Leeds to Barnsdale turnpike so it’s possible they may have made arrangements to be picked up at their front door. Alternatively they may have hired their own carriage or been loaned one by John Blayds.

Either the expense or the difficulty of arranging transport meant the Craigs had to leave behind much of their furniture and household effects. An announcement was made in the Leeds Intelligencer at the end of June 1834 for an auction to be carried out on Monday 7th of July by Thomas Lumb. The catalogue included silver plate, a two year old upright piano bought from John Broadwood & Sons in London, and a collection of books, paintings, prints and maps. There were also “philosophical instruments and apparatus” along with mahogany specimen cases showing John Kershaw Craig had an active interest in science, geology and natural history. Catalogues for the sale were available in Leeds, Pontefract and Wakefield.

A couple of months after Reverend’s Craig’s departure a testimonial was drawn up and signed by 130 of the Oulton parishioners. It was dated 15 September 1834 and expressed their “heartfelt conviction” that he was “a true and faithful shepherd of Christ’s flock.” They deeply regretted that his departure had deprived them of his invaluable services. The testimonial went on: “Wherever he goes he will carry with him the prayers and blessings of many in this village, who by Divine Grace, he has been the means of awakening from sin and establishing in the Truth.”

As was the case at Oulton very little was recorded about the Craig family’s time in Edmonton. Personally their third son was born in August 1836 whilst they were living at a house on Fore Street. Professionally, also in the summer of 1836, Reverend Craig applied to become a missionary at Demerara in the colony of British Guiana (now Guyana) on the northern coast of South America. He was supported by a letter from the Edmonton vicar, Dawson Warren, who wrote to Charles Grant otherwise known as Lord Glenelg, the Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. “I have uniformly found him a most able assistant and an invaluable friend. His abilities as a preacher, and his conduct as a man, have attratced the warmest regard of many who join with me in deeply regretting his departure,” wrote Warren.

As it turned out the application fell through. The following March Reverend Craig then expressed a desire to return to Yorkshire by putting his name forward as one of eight candidates to become the vicar at Leeds parish church. He may well have had the political backing of John Blayds and his brother Thomas but was unsuccessful with the trustees who made the decision. The winning candidate was Dr. Walter Farquhar Hook, previously the vicar of Coventry. He went on to be recognised nationally for his efforts to combat the rise of Methodism and other non-conformist sects in Leeds by building many new Anglican churches and schools as well as rebuilding the Minster.

The Reverend John Kershaw Craig achieved a very different form of notoriety! In May 1839 with “a very elegant and costly silver tea service with appropriate inscriptions” as a leaving present from his Edmonton parishioners, along with another testimonial, he left Middlesex for rural Hampshire. There he had been appointed by his old friend the Bishop of Winchester to be the vicar at the new church of St. John the Baptist at Burley near Ringwood in the New Forest. In a situation similar to that in Yorkshire many of the locals were attending dissenting chapels and the new church was part of an effort by the Church of England to win back a congregation and increase its income from donations at Sunday services.

All went well for the next few years and Reverend Craig appears to have become as well liked as he had been in previous parishes. John and Elizabeth’s fourth and final son, Bernard Riccarton Tudor Craig, was born in April 1840 and after living at rented farms the family moved into a fine house called Dilamgerbendi Insula at Picket Post north of Burley where they employed a number of live-in servants.

Then in February 1845 came a bombshell. Charges were brought accusing the Reverend John Kershaw Craig of “adultery, fornication and incontinence,” the last word referring to “a failure to restrain sexual appetite,” rather than the more modern meaning. According to statements, principally from several of his teenage female servants, he had been kissing them in the kitchen and getting into bed naked with them late at night whilst his poorly wife slept alone in her room. A farm labourer also alleged that in the summer of 1844 he had twice seen Craig having sex with one of the girls in nearby woods.

All this information was collated by a former attorney called George Rooke Farnall. He had subscribed to a fund to build the new church and lived in a large house at Burley Park surrounded by a 75 acre farm. In modern times these kind of allegations would be dealt with by the police but the course of action then was that Farnall wrote a letter to the Archbishop of Canterbury making the charges and demanding Reverend Craig be “canonically corrected and punished.” The Archbishop passed the allegations to the Bishop of Winchester who was duty bound to set up a commission of inquiry which consisted of the rural dean and three other priests.

The commission interrogated the witnesses at the nearby village of Ibsley over nine days and decided in May 1845 that there was a case to answer. With his reputation on the line Reverend Craig had again to sell most of his possessions to raise money to defend himself. After leaving Oulton he must have acquired some wealth by inheritance as the notice of a three day auction sale in June 1845 included many new items of mahogany furniture. There were also “three pictures by old masters”, a large finger organ, a phaeton carriage and a library of a thousand books including valuable editions of Greek and Latin classics.

Knowledge of the charges must have become quite widespread in Hampshire but using the Church Discipline Act Reverend Craig managed to persuade the commission of inquiry to hold the evidence sessions behind closed doors. It prevented reporters from publishing any titillating details of the allegations but as the Hampshire Gazette pointed out: ”As he has attempted to cover the charges against him with a veil of secrecy, the most extraordinary, and possibly exaggerated rumours are afloat as to the details of his presumed offices.”

The full case was then heard at the Arches Court starting in January 1846. It had jurisdiction over marriage disputes, church property and, as in this case, the morals of the clergy and laity. In court Reverend Craig said that George Rooke Farnall had expressed great personal enmity towards him although it wasn’t stated what had caused this. “All the charges have been wickedly and maliciously brought and are utterly false and unfounded,” he said. Claiming there were many inconsistencies in evidence from the witnesses he provided a signed retraction by one of them. He also pointed out the labourer who’d seen him in the wood was employed by Farnall.

The case dragged on at several hearings for nearly two years. As well as the sexual behaviour charges further allegations were brought by Farnall about Craig’s conduct of church services and the way he ran the village school. Eventually on 11 November 1847 after a lengthy summing up the judge, Sir Herbert Jenner Fust, decided there was some truth in the allegations. He passed a sentence suspending Reverend Craig from acting as a priest for two years along with a payment of £250 costs, although the lawyers’ fees must have been more than a thousand pounds on both sides.

Supported by his older brother, Edward, who had also had a career in the church, John Kershaw Craig had no other option than to appeal to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council. Consisting of judges sitting in the House of Lords it was the highest court in the country and in the British Empire. At its height it was said to be the final court for a quarter of the world’s population.

Pending the appeal Edward Craig, by then the perpetual curate at St. James’s, Pentonville in north London, set out to demolish the case against his brother in an 80 page book. It must have been written around Christmas 1847 after the Arches Court judgement and was presumably designed to raise funds for the appeal. Costing 2 shillings and 6 pence it was published on 15 January 1848 by William Benning, law booksellers on Fleet Street, and made no bones about the conduct of the case by Judge Jenner Fust.

Edward pointed out that George Rooke Farnall’s animosity towards his brother went back to 1840 when he had “put his fist” in John Kershaw’s face and threatened to knock him down. The charges, he wrote, were “absurd, scandalously false and groundless” as well as being “base insinuations, foul calumnies, and monstrously and hideously cruel.” Witnesses had perjured themselves and given contradictory evidence. The sentence was of “utter and absolute ruin” to his brother, his wife and children. The book also claimed that seven or eight female servants in Farnall’s employment had had to leave because they were pregnant.

Finally, after another lengthy delay and another hearing, the Privy Council judges gave their majority decision on 20 March 1849. Finding in favour of Reverend Craig they dismissed and eloquently demolished all the charges against him. After four years of trials and tribulations it must have been a great relief, although throughout he had maintained the support of his wife and a majority of his parishioners at Burley.

Meanwhile, in November 1848, George Rooke Farnall had been admitted to a private “lunatic” asylum at Brislington near Bristol where he died three years later. The cause of death was given as “paralysis,” a term commonly used for a patient suffering from syphilis.

After his wife passed away in 1858 John Kershaw Craig stayed on in Burley serving as the parish priest until he retired in 1886. He died there in 1889 about a month before his 88th birthday. His anonymous obituarist wrote: “He loved to organise old-fashioned fetes for the diversion of his parishioners, and even revived the Maypole. He sometimes gave a general invitation to the gipsies who rove the Forest, and hospitably entertained them. If the gatherings occasionally degenerated into drunken orgies, instead of being models of rural simplicity, it was not his fault.”

It’s not known if he ever returned to visit Oulton.