The paper mill in Woodlesford was in production for well over a century until it closed in about 1870. No photographs of the mill buildings have so far come to light but its chimney features prominently in views of Woodlesford taken before it was demolished in the 1960s. The mill is shown on several maps and plans drawn in the 18th century in connection with improvements to the Aire and Calder Navigation. Maps made in the 19th century by the Ordnance Survey show the same building at the end of Alma Street marked as Oddy’s Mill. After paper production ceased the mill was used for making matches and then as a chemical works.

According to Rothwell historian, Albert Brown, the paper mill was built by the Lowther family of Swillington House. It’s not known precisely when it opened but from entries in the Rothwell parish registers it appears to have been operating from at least the early 1730s. The first recorded paper maker was Ratcliff Manchister whose son, John, was baptised in December 1732. Ratcliff died the following November and his widow, Mary, remarried three years later. Another early paper maker was John Manchister, possibly Ratcliff’s brother. He had a son, also John, baptised in 1736. A generation later in the 1750s and 1760s John Procter and Issac Walton were recorded as paper makers living in Woodlesford.

From their profits in cloth trading William Lowther and his brother John acquired the Swillington estate in 1656 from Conyers Darcy whose family had been granted it shortly after the Norman conquest. William Lowther bought his brother’s share in 1658 and from the outset he exploited the coal which lay underground. The paper mill was probably built by Sir William Lowther, grandson of the original William, to supply paper for letters and accounts. Any surplus produced by the mill and not needed by the estate would have been sold to stationers and merchants in Leeds. It’s possible the mill also made coarser brown paper for wrapping cloth and other products.

Evidence the mill was in production in the 1740s comes from an agreement made with the Aire and Calder Navigation company dated 16th January 1743. It states: “The paper mill, at Woodlesford, shall have the use of the water in the Cut doing no damage to the Navigation but in times of scarcity of water the boats there navigating shall be the first to be served with water.”

The Cryer Cut, or canal, had been dug in the early 1700s to make it easier for boats to ply between Leeds and the coast. It was enlarged and moved slightly to the north in the 1830s leaving the old stretch of water to become a thin lagoon known as the “goit.” At the same time the lock was moved to the east and a new canal was made between Woodlesford and Lemonroyd so boats could completely avoid the river.

After supplying the land and capital to build the paper mill the Lowthers would have leased the enterprise to a man who employed his own workforce. It’s possible this originally may have been one of the Manchister paper makers referred to above but more likely it was Thomas Crampton. Little is known about him apart from the fact he was born about 1700 and in October 1727, at Rothwell, he married Ann Cockell. Parish records indicate they had at least five children – three boys and two girls.

One snippet of information comes from a Lowther estate account book which is now in the West Yorkshire archives. Written in ink, most likely on Woodlesford made paper, it shows rents collected across the estate by the agent William Sykes in 1745 and 1746. Of 18 Lowther properties listed in Rothwell parish Thomas Crampton was paying the most at £21 10 shillings a year, roughly equivalent to £10,000 today, so the paper mill must have been doing well.

Thomas Crampton’s eldest son, William, was only 25 years old when he died in December 1753 just a year after his marriage to Eleanor Nelson from Swillington. The second son, James, born in 1731, appears to have moved away so it was left to the youngest, Thomas, born in 1734, to follow his father into the paper making business.

He married Ann Birks from Fleet Mills in July 1758 and over the next twelve years they had five children – Thomas, Joseph, Esther, Ann and William. During this period the family name, as recorded in the parish registers, seems to have subtly changed from Crampton to Crompton although it’s not known whether that was by design or accident.

1771 was a bad year for Ann Crompton. In May she lost her youngest child who was just a year old and then in August her husband died. As a widow it appears she bravely took over the management of the paper mill, probably with the help of a foreman.

In 1774 the Aire and Calder Navigation were making plans to re-route and extend the Cryer Cut towards Methley and it looked as though part of the paper mill’s drying house would be demolished.

The new canal would also have run through an orchard between the Crompton’s house and the mill. More seriously the water supply to the mill would have been jeopardised. The Reverend Sir William Lowther, who had inherited the estate from his childless cousin, didn’t object in principle to the plans, but in a letter to his agent he asked him to make sure the water supply was secured by lobbying for a clause to be inserted into the parliamentary bill granting the new route. In the end the Navigation decided not to proceed with their plan until much later when a different route was chosen for the new cut.

Not that it was plain sailing. Around this time the Lowther estate sold the land on which the mill stood to the Navigation and, according to Albert Brown, in October 1779, Mrs. Crompton claimed recompense from them for “some damage done to her paper mill at Woodlesford.” It was probably caused by flooding and the company instructed their engineer, John Gott, to settle with her.

No records of Ann Crompton’s eldest son, Thomas, seem to have survived, but it looks as though her second, Joseph, joined the business. He was recorded as a master paper maker in 1803 and his name also appears in the Commercial Directory of 1814 – 15. When he died and was buried at Rothwell, at the age of 54 in 1816, the notation Esquire was used in the burial register. It suggests he had high status in the community and was probably a relatively wealthy man, although he appears to have been unmarried.

Ann’s third child, Esther, was born in 1766 and it was through her that the profits of the Woodlesford paper mill passed to later generations.

On 11 July 1791, at Rothwell, she married Thomas Oddie who was about a year younger than her. The wedding was sufficiently important to be reported in the Leeds Intelligencer newspaper on the 2nd of August: “A few days ago was married Mr. Oddie, Officer of Excise, at Rothwell, to Miss Crompton, of Woodlesford.” Witnesses to the wedding were Esther’s brother, Joseph, and her younger sister, Ann, along with a cousin, Ann Green, daughter of Luke Green, a Woodlesford yeoman farmer.

Thomas Oddie and Esther Crompton probably met through his job when he visited the mill to collect the tax on paper which became known as a “tax on knowledge.” After their marriage they went to live in Otley, possibly because he came from there, or because of his work. Their first son, William, was born just over a year after their marriage and a second, Joseph Crompton Oddie, followed in 1794. Both were baptised at Otley.

Tragedy then struck the family when Thomas died in June 1795. He was only 30 years old but it’s not known if he succumbed to an illness or died as a result of an accident. His body was brought back for burial at Rothwell where the register states he was “from Otley.”

Esther brought her sons back to Woodlesford to live with her mother and brother and as they grew up they would have been gradually introduced to the routines of the mill which by then employed about 20 people. Their granny passed away in 1808 followed by their uncle, eight years later. It would have been at some point before his death that William and Joseph Crompton Oddie assumed full responsibility for the business, no doubt with guidance from their mother.

They were certainly in charge in May 1817 when they took action against James Nicholls, a Leeds bookseller, stationer and printer. He owed them for supplies of paper and, with the help of solicitors Atkinson and Bolland, they petitioned to have him made bankrupt so they could get some of their money back. The brothers were also investors in the Norwich Union Fire and Life Society.

All seemed to be going well but then, in September 1818, William died in a boating accident off Scarborough.

According to newspaper reports he was with two men from York, accompanied by two boatmen, on a sightseeing trip to Filey. They had landed on rocks known as Filey Bridge, or Brig, and were about a quarter of a mile out to sea on their way back to Scarborough for dinner when the boat’s sail was caught by a gust of wind and “overturned in an instant.”

As the others clung to the boat William Oddie decided to swim towards the shore but he had only gone between twenty and thirty yards when his strength failed and the weight of his clothing caused him to sink lower in the water. He made an effort to return to the boat but was so exhausted “he shrieked and was seen no more.”

The other men clung on for about half and hour before they were rescued by a sloop and taken back to Scarborough. As the Stamford Mercury put it: “Mr. Oddie was possessed of a handsome fortune, and was the hope and joy of a widowed mother.” Other papers reported a search for the body had been “without success.”

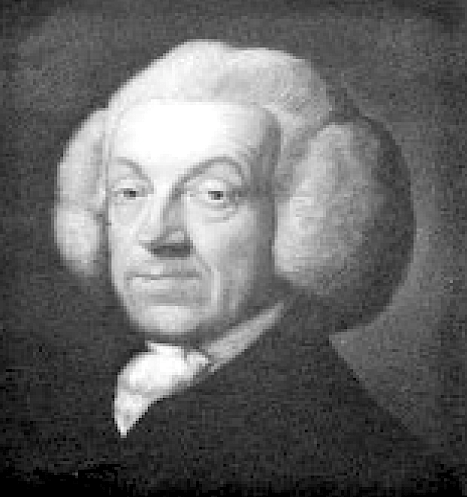

With the death of William the paper mill was left solely in the hands of Joseph Crompton Oddie who was 24 years old. His mother lived on until 1832 but by all accounts it was her son who was the driving force behind the business until its decline in the 1860s. He never married and lived with servants in a large house called The Laurels at the end of Alma Street overlooking the mill. An early 19th century document described it as a dwelling house, barns and stables.

Joseph was well known for his charitable donations. For instance in 1819, he and the Woodlesford pottery owner Joseph Wilkes gave a donation of £2 2 shillings each to the Leeds General Infirmary. In 1847, during the Irish potato famine, he gave £10 to a Leeds fund “for the relief of destitute persons in Ireland and Scotland.” As an old man he was high on the list of subscribers to the new Mechanics’ Institute in Rothwell, now the Windmill Youth Centre. He also gave anonymous handouts to the local poor.

Despite producing large quantities of paper over the years no written records or accounts from the mill itself have survived so it’s only possible to catch glimpses of what went on there from census entries and other sources.

The 1841 census shows Joseph Crompton Oddie living with two servants. Grace Brook was 30 and Ann Thompson from Hunslet was 23. For some reason the household was omitted from the 1851 census but ten years later Ann was still there as housekeeper along with her younger sister Martha. Both continued to look after Joseph until his death after which they retired to live in a house on Applegarth with another sister, Maria.

A list of those who were working at the mill, taken from the 1851 census, is at the bottom of this page along with their ages and birthplaces. There were 12 men and 17 women connected with the mill in Woodlesford and Oulton, although one was retired and four were put down as paupers, the forerunners of today’s state pensioners. They would have been living on small amounts of money handed out by parish officials known as “Overseers of the Poor.” Jospeh, along with farmer David Chadwick, was appointed to the role for Oulton and Woodlesford in 1847 but it’s not known how long he served for.

According to Albert Brown, as well as the paper mill, Joseph was also involved with lace making which took place in a large stone building at the end of Alma Street, now converted into cottages.

On Tuesday 22 August 1848 thieves broke into the paper mill and stole some copper scales, weights and other articles. The Leeds Mercury reported that James Adams was caught at the King’s Arms at Bank in Leeds on the following Friday evening. Patrick Rawling, who lived next door, was also arrested after a pair of copper scales were thrown out of his window as Adams was being detained. They were brought before the magistrates in Leeds and committed for trial at the West Riding sessions.

Another source is the diary of Edward Metcalf, who lived near to the mill at the new Woodlesford lock from 1856. He records that in 1859 “the mill was rebuilt; a nearby stream was diverted in a new cutting and Mr. Oddie bought all the land adjoining.”

In July 1860 Joseph was listed as the owner of the Cutside Mill when, with over 160 paper manufacturers from across the country, he signed a petition to the government protesting against a proposal to lower the import duties on foreign made paper. At the time they had to import rags from Europe because there was a domestic shortage but the Continental countries either banned their export or charged high export duties. The British firms complained this put them at a disadvantage and any lowering of the cost of foreign made paper threatened to put many of them out of business.

The 1861 census shows the extent of Joseph’s wealth. By then he was described as a farmer and a paper manufacturer. 27 people were working at the mill – 7 men, 15 women, and 2 boys. With 221 acres he was probably the second largest landowner in the district after John Calverley of Oulton Hall. Some of it was let to tenants but on his own farm he employed seven men and a boy. In December of 1861 he was commended at a Leeds cattle show for two of his short horn cows.

Also that month, on Tuesday the 3rd, there was an accident involving one of the mill’s workers. As was common there was a dense fog around the canal and river and people could hardly see to make their way. It was so bad that boats couldn’t travel from Leeds.

Alexander Gleddon, who was 65, was walking on the steep road on the approach to the mill when he fell down the embankment. He was taken to the Leeds Infirmary where a fractured skull and an injured spine were diagnosed but he died a few days before Christmas.

Two years later, at about 9 p.m. on Wednesday 25 February 1863, the mill caught fire, the second time it had happened since 1853. It took about three hours to put the blaze out with the assistance of a fire engine from the brewery.

One of the closest buildings to The Laurels was the Boot and Shoe Inn. A building on the same site is clearly marked on Teal’s 1807 map but it seems Joseph Crompton Oddie paid for it to be rebuilt in the 1860s. The foundation stone was laid on 6 June 1864. According to Edward Metcalf, the new landlord, John Ingham, and his family, “have gone into Mr. Oddie’s coach house which he has made very comfortable for them ’til their new house is built.” As well as becoming a beer house keeper John Ingham was also a joiner and had lived previously in the centre of Rothwell.

A serious incident came in February 1866 when three days of stormy weather caused damage across England. On Wednesday 7 February in the Leeds area there was heavy rain during the night. Then during the day there was continuous rain with thunder and lightning followed by a hail storm in the evening. Many houses had their windows broken.

The Leeds Mercury reported: “About noon, Mr. Oddie, of Woodlesford, had a most providential escape. He had just been writing at a table near the window, and was putting a book away, when he was almost blinded by a flash of lightning, accompanied by a terrific clap of thunder.”

“On recovering from the shock he found that the electric fluid had torn down the bell wires, and in some places stripped off the room paper. Above one hundred panes of glass were smashed, and one attic window forced out bodily. Outside, a tall poplar was cut in twain transversely, the upper half was rent longitudinally, and one part had fallen so plumb as to remain uptight against the lower half of the tree. The other part was shivered into fragments and scattered on all sides. The north west angle of the house was also injured.”

In the early 1870s the mill was closed down although it’s not known why. It could simply be because Joseph Crompton Oddie was getting old and wanted to retire. The mill may also have gone into decline following the death, in 1860, of the foreman, John Denkin. He’s believed to have taken over from his father who he was named after.

John Denkin senior was born in about 1750 and his occupation was given as a papermaker when he married Mary Bradley at Halifax in 1777. Their wedding was witnessed by another papermaker, Robert Bradley, who was probably Mary’s brother or possibly cousin. All three appear to have moved to Bradfield parish to the north west of Sheffield where Robert became the proprietor of paper mills at Damflask and nearby Storrs.

John Denkin junior was baptised in Bradfield parish in 1794 but Robert Bradley went bankrupt a year later prompting the Denkins to move to Woodlesford where John senior is recorded in the Rothwell church registers in 1798. By 1832 the Denkins were wealthy enough to buy seven cottages at the junction of Applegarth and Church Street in Woodlesford, part of the estate built up by pottery owner William Wilks which had passed to his son Joseph. The cottages became known as Denkin’s Fold and then Taylor’s Yard until they were demolished in 1939.

Another “victim” of the closure of Oddie’s paper mill was James Smith Abbey. After serving an apprenticeship at the mill in 1865 he married Emma Boys, the daughter of a railway labourer. Five years later though, with three daughters to provide for, they left Woodlesford for work at a paper mill at Afonwen in Flintshire. Then, after another move to a mill at Rhostyllen near Wrexham they eventually ended up at High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire where James continued in the paper making trade until his death in 1908.

Towards the end of his life Joseph Crompton Oddie contributed £3000 to the construction of Woodlesford church. He died in April 1874.

An obituary in The Rothwell Times described his funeral which was of “a most thorough and costly character.” Henry Bentley was one of the pall bearers. “The poor of Woodlesford will keenly miss the liberal doles which the old gentleman frequently sent them; extremely careful and somewhat eccentric in his habits, he has left behind him a large amount of property.”

In his will he was wealthy enough to leave legacies and annuities to his servants and other locals as well as relatives. He bequeathed The Laurels, along with his furniture, effects and an annuity of £400 to his cousin, James Oddie, for life. He had been an insurance agent in Liverpool and he and his wife, Ellen, left their home at Hooton near Ellesmere Port and moved to Woodlesford.

Five years after Joseph Crompton Oddie’s death, in March 1879, James advertised the mill “to be let.” At first nobody appears to have been interested and the adverts continued in the Leeds newspapers until at least 1883. In 1890 the lease was taken by the Seanor match manufacturing family from Rothwell who used the mill to make firelighters and matches. A report in the Rothwell Times stated that alterations had been going on for several weeks to install machinery for the production of firelighters or “grids” which had “such celebrity as to demand the opening of these new premises.” A 40 horse power stationary steam engine and boiler were installed along with saws and a production line for making, dipping and packing the firelighters. The Seanors had already expanded their business from Rothwell to Bootle near Liverpool. “This makes the fourth factory under Messrs Seanor, and its introduction into Woodlesford will no doubt be warmly welcomed as a new means of earning honest wages,” declared the paper. Production started on Tuesday 17 June 1890 and lasted until about 1907.

The other main beneficiary of Joseph Crompton Oddie’s will was his cousin’s son, Alfred Dawson Oddie, a commercial clerk in Liverpool, but he died suddenly in October 1874, at the age of 32, just a couple of months after the will was proved. After the annuities and legacies the balance of the personal estate was to be invested in freehold property where it was to accumulate for ten years before being settled on Alfred Dawson.

In the event a large portion of the estate appears to have gone to Alfred Dawson’s younger brother Edward. Some also appears to have been settled on another brother, Thomas, who became an executor and trustee along with the Oulton land agent John Farrer.

After marrying and having a son and two daughters Edward became estranged from his wife who eventually took out an action in the Court of Chancery in 1902. By that time she was living in Malvern and he was in London, the sole occupant of a large house in Guilford Street in Bloomsbury and described in the census as a gentleman.

In what was described as a friendly action Emily Ann Oddie formally sued the trustees of the estate so that it could be handed over to new trustees according to an amicable arrangement that had recently been reached. Edward, it was said, had been taking out mortgages against the estate and his wife had already persuaded the trustees to limit his income to £6 a week.

The court was told she was seeking to protect the income of her son, Alfred Gerald Oddie, who had just graduated from Oxford University and was on a voyage to New Zealand for the benefit of his health. She also wanted provision to be made for her daughters who only had £3000.

By that time the total estate was worth £146,000, roughly the same as £8 million today. Still held in trust was land at Woodlesford, Rothwell, and Llangollen in Denbighshire. £104,000 (£6 million) was personal estate, including £101,000 (£5,700,000) in Leeds Corporation stock. The total annual income was £5000, equivalent to about £285,000 today. Not bad for a farm and a small paper mill by the side of the canal!

Paper mill workers in 1851 with their ages, occupations and birth place.

Mary Goodall, widow, 83, pauper (miller), Middleton. Martha Goodall, 40, paper sorter, Woodlesford. Thomas Bottomley, 21, paper maker, vat man, Goose Eye, Keighley. William Gibson, 46, paper maker and pottery manufacturer, 46, Woodlesford. (William’s paper making may have been separate to that of J.C.Oddie.) Sarah Abbey, widow, 38, rag sorter, Methley. Mary Mason, widow, 58, pauper paper maker, Whixley near Harrogate. William Sewter, 29, paper finisher, Norwich. George Smith, 63, engine man, Pool. Jane Lee, 42, rag sorter, Syke House near Doncaster. Mary Ann Jordan, 35, rag sorter, Methley. Samuel Marsden, 38, engine man, Bradford. William Kirton, 39, vat man, Topsham in Devon. Elizabeth Abson, 25, picker or sorter, Woodlesford. John Denkin, 54, foreman, Sheffield. James Gough, 91, retired paper maker, Barwick-in-Elmet. Mary Ward, 22, rag sorter, Woodlesford. Ann Ward, 22, rag sorter, Halton. Elizabeth Johnson, 61 pauper paper maker, Horsforth. Susan Clareborough, 30 paper sorter, Horsforth. John Bailey, 36, paper drier, Bersham near Wrexham. Mary Ellis, 21, paper sorter, Woodlesford. Thomas Yeadon, 66, paper drier, Woodlesford. Sarah Bleasby, 59, rag sorter, Woodlesford. Ann Walton, 30, rag sorter, Oulton. John Whitehead, 77, pauper paper maker, Oulton. Alexander Coombs, 32, vat man, Eynsford in Kent. Elizabeth Coombs, 44, paper cleaner or picker, Woodlesford. Charles Coombs, 18, paper layer, Maidstone, Kent. Jane Aspinall, 53, paper cleaner, Swinton. Ann Hingham, 49, employed at paper mill, Oulton. Ann was the only worker who lived in Oulton. All the others were in Woodlesford.